|

| Photo by Dan Eldon |

In order to even begin to understand the recent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, I’ve come to realize that there’s a lot you first have to forget. Forget Bush. Forget 9/11. Forget Obama. Forget Osama. Forget everything you thought you knew about why America went there – oil, Saddam, democracy, security – and just listen to the stories of those that were there.

But soldiers’ stories are not always easy to come by. Most would just as soon forget, or at least move on, and understandably so. What good could come of talking about it, especially to a public still hanging on to the idea that everything’s okay?

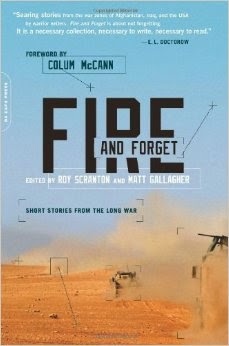

Well, the silence has finally been shattered. And for those who are ready to listen, I highly recommend Fire and Forget, a collection of 15 short stories written by US combat soldiers (and one army spouse). This book is not a military history. There are no political theories espoused. Rather, every story in this book brings you closer to the chaos – and to the understanding.

Well, the silence has finally been shattered. And for those who are ready to listen, I highly recommend Fire and Forget, a collection of 15 short stories written by US combat soldiers (and one army spouse). This book is not a military history. There are no political theories espoused. Rather, every story in this book brings you closer to the chaos – and to the understanding.

It’s a stripped down, naked, and, most of all, extremely honest account of what goes on inside a soldier’s head during battle, in their down time, and after they return home. One minute you’re on the battlefield and the next you’re in the bedroom, expected to be able to kill and love at the same time. For many, the fighting never stops and we get an intimate look at the re-integration process. In one scene, a soldier returns home from war to find that his old dog, Vicar, is sick and dying. When it comes time to put the dog down, his wife, Cheryl, says:

"I’ll take him to the vet tomorrow."

I said, "No."

She shook her head. She said, "I’ll take care of it."

I said, "You mean you’ll pay some asshole a hundred bucks to kill my dog."

She didn’t say anything.

I said, "That’s not how you do it. It’s on me."

(from Redeployment, by Phil Klay)While it’s clear that the adjustment isn’t going to be easy, there’s a strange sense in which the experience of war not only makes one more human, but can also make a person more humane.

As civilians, the worst thing we can do is to forget about the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, regardless of whether we agreed with them or not. That’s why it’s time to Read & Remember the stories of the men and women that were there. They have something to say.

Postscript

Friends, again, I can’t recommend this book enough. There are some great insights into the human soul and the writing is fantastic. Here are two more excerpts, but believe me there were many to choose from:

from Smile, There Are IEDs Everywhere, by Jacob Siegel

"For us, there had been no fields of battle to frame the enemy. There was no chance to throw yourself against another man and fight for life. Our shocks of battle came on the road and it could always explode. There was no enemy: we had only each other to hate."

also from Redeployment, by Phil Klay

"So here’s an experience. Your wife takes you shopping in Wilmington. Last time you walked down a city street, your Marine on point went down the side of the road, checking ahead and scanning the roofs across from him. The Marine behind him checks the windows on the top levels of the buildings, the Marine behind him gets the windows a little lower, and so on down until your guys have the street level covered, and the Marine in the back has the rear. In a city there’s a million places they can kill you from. It freaks you out at first. But you go through like you were trained and it works.

In Wilmington, you don’t have a squad, you don’t have a battle buddy, you don’t even have a weapon. You startle ten times checking for it and it’s not there. You’re safe, so your alertness should be at white, but it’s not.

Instead, you’re stuck in an American Eagle Outfitters. Your wife gives you some clothes to try on and you walk into the tiny dressing room. You close the door, and you don’t want to open it again.

Outside, there’re people walking around by the windows like it’s no big deal. People who have no idea where Fallujah is, where three members of your platoon died. People who’ve spent their whole lives at white.

They’ll never get even close to orange. You can’t, until the first time you’re in a firefight, or the first time an IED goes off that you missed, and you realize that everybody’s life, everybody’s life, depends on you not fucking up. And you depend on them.

Some guys go straight to red. They stay like that for a while and then they crash, go down past white, down to whatever is lower than “I don’t fucking care if I die.” Most everybody else stays orange, all the time.

Here’s what orange is. You don’t see or hear like you used to. Your brain chemistry changes. You take in every piece of environment, everything. I could spot a dime in the street twenty yards away. I had antennae out that stretched down the block. It’s hard to even remember exactly what that felt like. I think you take in too much information to store so you just forget, free up brain space to take in everything about the next moment that might keep you alive. And then you forget that moment too, and focus on the next. And the next. And the next. For seven months.

So that’s orange. And then you go shopping in Wilmington, unarmed, and you think you can get back down to white? It’ll be a long fucking time before you get back down to white."

No comments:

Post a Comment